Recovered and Repressed Memories: Fact or Myth?

How far can your mind go to protect you in the face of trauma?

We’ve all had those moments where we wish we could forget something ever happened, whether from embarrassment, shame ,guilt, anger, or heartbreak, but can you forget something that completely? If you go with the definition of repression that involves a deliberate conscious effort to remove, block, or bury the memories and includes active avoidance, then maybe you can accomplish that, but what if it was something really bad? Something so awful that your mind represses the incident(s) as an automated defense mechanism to protect your mind, and possibly your sanity. Can you repress and effectively forget something as awful as sexual abuse? The answer: possibly

Your mind represses certain traumas for reasons of pure survival.

Suzie Burke

How survivors of trauma remember or forget their most terrifying experiences lies at the core of one of the most bitter controversies in psychiatry and psychology: the debate regarding repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse. Most experts hold that traumatic events, those experienced as overwhelmingly terrifying, threatening to our safety, or as far as life-threatening, are remembered very well; however, traumatic dissociative amnesia theorists disagree (McNally, 2007). The traumatic dissociative amnesia theorists claim “that a sizable minority of survivors develop “massive repression” of their trauma, making it difficult for them to recall it until it is safe to do so, often many years later. In fact, some believe that the more traumatic an event is, the more likely some survivors will be unable to remember it (McNally, 2007).”

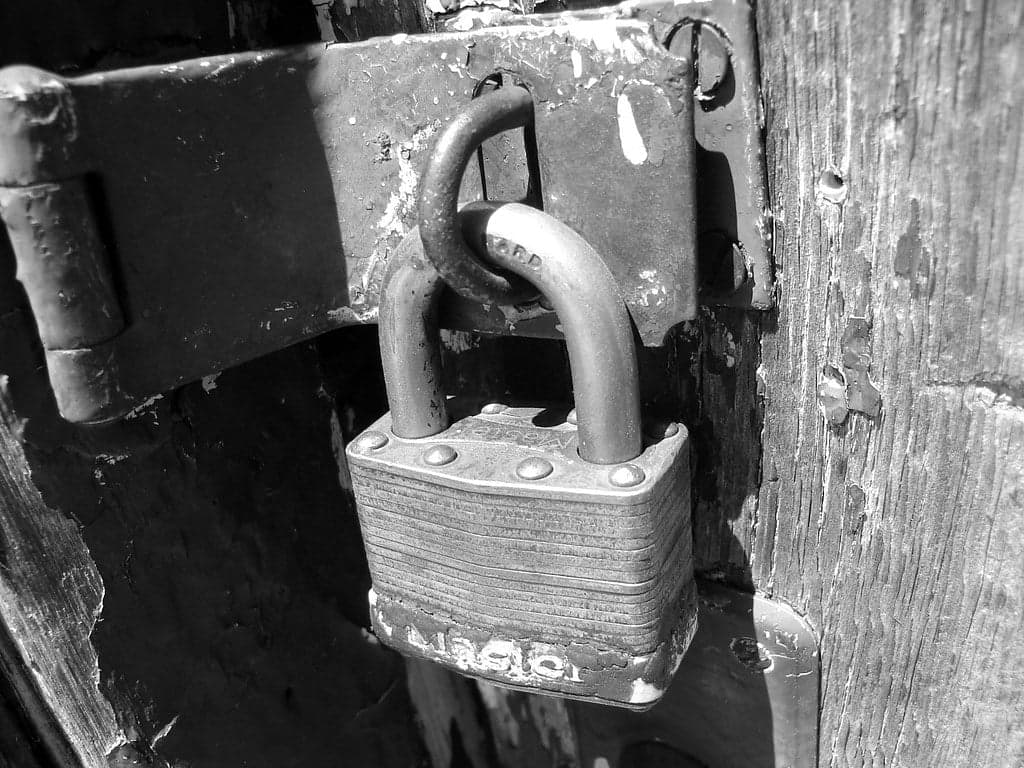

A recovered memory is defined as, “A forgotten memory of a traumatic event (as sexual abuse) experienced typically during childhood and recalled many years later that is sometimes held to be an invalid or false remembrance generated by outside influences (Merriam-Webster, “Recovered Memory”).” Some repressed memories can be recovered unwillingly and randomly through spontaneously recovered memory. This can happen in two ways; the first is randomly by things that are linked to the trauma; smells, tastes, touches, sights, noises, the looks people give them, if someone looks like the person who abused them, situations, tones of voice, body language, and more. The second is that as the person gets more time between them and what happened, the lock on that mental door can start to loosen, little by little. Some things can slip through. A flash of an image here, a remembered sensation there, and it can progress further. Both can cause a lot of confusion, fear, rage, shame, helplessness, and a feeling like your losing yourself under this sudden emotional onslaught.

For those of you who wouldn’t want to go through that but still want to heal, there’s some bad news. According to the traumatic dissociative amnesia theorists, remembering the incidents that caused the dissociative amnesia is the only effective way to heal from it. (McNally, 2007) Suzie Burke, R.N. Ph.D., author of Wholeness: My Healing Journey from Ritual Abuse states in her book, “That is the problem with repressed memory and dissociative identity disorder. Your mind represses certain traumas for reasons of pure survival. And then you learn that to survive as an adult, you must uncover the memories, find the parts, and relieve the traumas. The contradiction is almost too much for the mind to comprehend and for the heart and soul to endure.”

Purposefully trying to recover the memories can be done through techniques like hypnotherapy, but that is also a highly suggestible method that can accidentally create false memories, as can drug-assisted interviews, and guided visualization. That possibility of creating false memories is actually what sparked the ‘memory wars’ between the fields of psychology and psychiatry in the 90s. A surge of people came forward about sexual abuse that they only had remembered through therapy using one or more of the methods listed above. The False Memory Syndrome Foundation started using and coined the term false-memory instead of recovered memory, as they advocated on behalf of the people that claimed they were being wrongly accused of committing the abuse (False Memory Syndrome Foundation, 2006).

As researchers began to create studies focusing on how we create, forget, and remember memories, the tension between the fields began to ease. While there are still various opinions on the subject, there is a relatively peaceful agreement that while some recovered memories are false, there are ones that are real (Geraerts & Van Meggelen, 2019). Sigmund Freud introduced the concept of recovered memories in 1896, but at the time he couldn’t back up his theory with research and abandoned it two years later, believing that he had been wrong (Triplett, 2005). Freud believed that psychological problems can be converted into somatic manifestations, such as hysteria and obsessional neurosis that then affect the individuals throughout their life, even if they never remember what happened. Despite Freud having not been able to prove his seduction theory about recovered memories and gave up on it, his theory laid the foundation for the research that we have today and has helped many people understand themselves and receive the help they otherwise would not have. Have you ever had something that feels like it could be a repressed memory? When you ponder over the sense that something is being hidden in your mind, does it conjure an image such as a door with or without a lock, a box with or without a lock, or is it a strong instinct that it is there somewhere? Both are very common ways to describe how having repressed memories feel. What emotions did recognizing the repression provoke? How did you handle that information? Lastly, and most importantly; Are you ready to take the steps needed to heal from the trauma by opening that door?

False Memory Syndrome Foundation. (2006). EARLY HISTORY OF THE FALSE MEMORY SYNDROME FOUNDATION. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from http://www.fmsfonline.org/index.php?about=EarlyHistory

Geraerts, E., & Van Meggelen, M. (2019, November 18). Repressed and Recovered Memories. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199828340/obo-9780199828340-0035.xml.

goodreads. (n.d.). Suzie Burke (Author of Wholeness). Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/4143111.Suzie_Burke.

McNally, R. J. (2007, September). Dispelling Confusion About Traumatic Dissociative Amnesia. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(11)61370-0/fulltext.

Recovered Memory. (n.d.). Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/recovered memory.

Triplett, H. (2005, June 22). The Misnomer of Freud’s “Seduction Theory”. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://muse.jhu.edu/article/184074/pdf.